Un voyage en Chine

Extrait de VOYAGE EN CHINE ET EN MONGOLIE

de M. de Bourboulon, ministre de France et de Madame de Bourboulon, 1860-1861. par Achille POUSSIELGUE. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 77, Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris, 1866, 468 pages.

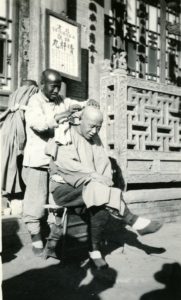

Tous les hommes se rasent la tête, à l’exception d’une couronne sur le sommet du crâne, dont ils se laissent croître les cheveux dans toute leur longueur. Il est de règle dans la bonne société de se raser tous les dix jours ; c’est un soin de propreté auquel aucun Chinois ne saurait manquer. L’usage de porter la queue a été imposé aux indigènes par la dynastie mandchoue ; sous les empereurs de race chinoise, les hommes laissaient pousser toute leur chevelure qu’ils réunissaient en touffe sur le sommet de la tête au moyen d’un nœud d’étoffe. Les rebelles Tai-ping n’ont pas manqué de revenir à cette coiffure des anciens temps qu’ils ont adoptée comme signe distinctif, et massacrent impitoyablement tous ceux qui ne sont pas coiffés comme eux.

Dans le nord où les rebelles n’ont pas encore pénétré, se laisser croître les cheveux est un signe de deuil ou d’extrême pauvreté ; les prêtres font seuls exception : ceux de Lao-tse portent leur chevelure, les bonzes sont complètement rasés. Pour être à la mode, il faut que la queue atteigne au moins un mètre de longueur, et, comme le cas est rare, les jeunes gens élégants allongent indéfiniment la leur avec des nattes qu’ils achètent aux barbiers. Les mandarins sérieux, les grands dignitaires la portent très courte pour montrer leur mépris pour les supercheries de la mode ; ceux qui sont chauves se contentent d’une queue en soie noire attachée sous leurs chapeaux.

Les Chinois ont peu de barbe, quelques longs poils sous le nez et au menton, mais à cause de cette rareté même, ils y tiennent extrêmement. Le dernier empereur Hien-foung avait trente-sept poils de chaque côté de sa moustache ; son barbier eut le malheur, un jour en la cirant, d’arracher un de ces augustes poils ; l’empereur, qui n’avait plus son compte, se mit dans une fureur extrême ; jamais, même pour les affaires les plus graves de l’État, pour les progrès croissants de la rébellion, on n’avait vu le souverain si en colère ! Bref, le barbier fut condamné à avoir la tête tranchée !

Cette mode de la queue, sans inconvénient dans les pays chauds, cause des rhumes fréquents pendant les froids hivers de Pékin. Pour couvrir le tour de leurs oreilles qui est rasée, les Chinois s’attachent autour du cou au moyen d’un ruban de soie des oreillettes doublées en fourrure. Les lunettes également doublées en drap protègent les yeux contre la réverbération du soleil. Un capuchon rouge ou bleu se rabat à volonté sur la tête qui est coiffée d’un chapeau dont les revers sont en fourrure. Le luxe des fourrures est porté au plus haut point chez les gens riches qui s’en enveloppent tout entiers en hiver. Cela tient à ce qu’ils ne se chauffent jamais chez eux où ils ne font pas même de feu. Comme ils ne connaissent pas les gants, les revers de leurs manches sont très larges et couvrent leurs mains en se rabattant.

SOCIAL LIFE OF THE CHINESE,

with some accounts of their religious, governmental, educational and business customs and opinions with special but not exclusive reference to Fuhchau, par Rev. Justus DOOLITTLE (1824-1880). Harper & Brothers, New York, 1865. Volume II, 490 pages + illustrations. Réimpression par Kessinger Publishing’s rare reprints.

The tonsure of the common people and mandarins, in disctinction from the tonsure of the members of the Tauist and of the Buddhist priesthood, consists in shaving the whole head with a razor once in ten or fifteen days, excepting a circular portion on the crown four or five inches in diameter. The hair on this part is allowed to grow as long as it will grow, and is braided into a neat tress of three strands. It naturally falls down the back. The lower extremity of the cue is securely fastened with coarse silk so that it will not unbraid. The ends of the silk are left dan-gling. When the cue or braid of hair is not of itself long enough to suit the fancy of its owner, it is lengthened by braiding in it some pair which has been combed out of other people’s heads, and arranged with great care in bunches for this use. The ambition of some is not satisfied until it is made to reach down within a few inches of the ground. When at work, and at other times when the cue would be troublesome, it is coiled about the head or thrown around the neck ; but to appear in the presence of their superiors or their employers with the hair thus coiled indicates a want of good manners.

Shaving the head, as above described, is practiced by all classes except females, Tauist priests, Buddhist nuns, and Bud¬dhist priests, and rebels against the present government. Females, unless they are Buddhist nuns, are permitted by custom and by law to wear their hair without braiding it into a cue. If they become such nuns, they must shave off all the hair from their heads every ten or fifteen days. Tauist priests either shave their hair like the common people, or they do not shave at all. The hair, left long, they never braid like the common people, nor is it left to dangle down the back, but it is coiled around on the top of the head in a manner peculiar to their sect. Priests of the Buddhist religion shave of all their hair as smoothly as possible two or three times per month. The reason why the Buddhist priesthood shave their heads in this manner is explained by some to be to indicate their desire to put away from them every thing of this world ; they do not claim as their own even their own hair.

The tonsure of t he common people is not a religious habit, nor is it originally a Chinese fashion. The first emperor of the present dynasty, who began to reign in 1644, having usurped the Dragon Throne, determined to make the tonsure of Manchuria, his native country, the index and proof of the submission of the Chinese to his authority. He therefore ordered them to shave all the head excepting the crown, and, allowing the hair on that part to grow long, to dress it according to the custom of Manchuria. The Chinese had been accustomed, under native emperors, to wear long hair over the whole head, and to arrange it in a tuft or coil on the head. As might be expected, the arbitrary command to change from the national costume to the shaven pate and the dangling cue was quite unwelcome. The change was gradual, but finally prevailed throughout the empire — so gradual that at the commencement of the reign of Kanghi, the second Tartar emperor, very few at Fuhchau had adopted the custom of their conquerors. At first, those who shaved their heads and conformed to the laws received, it is said, the present of a tael of silver ; after a while, only half a tael, and then only a tenth of a tael, and afterward only an egg. Finally, even an egg was not allowed.

he common people is not a religious habit, nor is it originally a Chinese fashion. The first emperor of the present dynasty, who began to reign in 1644, having usurped the Dragon Throne, determined to make the tonsure of Manchuria, his native country, the index and proof of the submission of the Chinese to his authority. He therefore ordered them to shave all the head excepting the crown, and, allowing the hair on that part to grow long, to dress it according to the custom of Manchuria. The Chinese had been accustomed, under native emperors, to wear long hair over the whole head, and to arrange it in a tuft or coil on the head. As might be expected, the arbitrary command to change from the national costume to the shaven pate and the dangling cue was quite unwelcome. The change was gradual, but finally prevailed throughout the empire — so gradual that at the commencement of the reign of Kanghi, the second Tartar emperor, very few at Fuhchau had adopted the custom of their conquerors. At first, those who shaved their heads and conformed to the laws received, it is said, the present of a tael of silver ; after a while, only half a tael, and then only a tenth of a tael, and afterward only an egg. Finally, even an egg was not allowed.

The law requiring the people to shave the head and braid the cue was not often rigidly enforced by the penalty of immediate death, but it became very manifest that those who did not conform to the wishes of the dominant dynasty would never become successful in a lawsuit against those who did conform, nor would they succeed at the literary examinations. Government favor, as regards lawsuits and literary examinations, was shown to those who conformed to the regulations of the government. Some of the proud literati and gentry absolutely refused to conform to the degrading and foreign custom, and the result was they lost not only their long hair, but their heads. It has been facetiously remarked by somebody in regard to this matter, that there was more than one example of a man ‘strangled by a hair’.

At the end even of the long reign of Kanghi the change was not completed ; but during the reign of his successor, the coil of long hair, according to the fashion of the Ming dynasty, completely gave place, in this part of the empire, to the shaven pate and the braided cue, such as are worn by the chiefs of the Manchu dynasty. Ever since, in sections of the empire loyal to the reigning family, the present fashion of the tonsure and the cue has been accepted by the Chinese as the badge of servitude to the Tartars. Cropping or cutting the hair in any way like the prevailing fashions in Europe and in America is entirely unknown among the Chinese.